(1243-1314 e.v.)

by T. Apiryon

Jacques de Molay. Twenty-second and last Grand Master of the Knights Templar. See Part III of The Heart of the Master.

The Knights Templar were founded in 1118 e.v. to protect pilgrims on their way to Jerusalem, and established their headquarters at the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem. The Order lasted 189 years and became one of the wealthiest and most powerful single institutions in Europe.

The Knights Templar were officially recognized as an Order by Pope Honorius in 1128 with the enthusiastic support of King Baldwin II of Jerusalem and Bernard de Clairvaux (later St. Bernard). They were given their first land, their Rule, and their Habit. The Rule was based on that of the Cistercian Order, and the Habit was a plain white mantle with a red cross. Their banner, called the Beauséant, consisted of two vertical bars, one black and one white. The word Beauséant was also the Templar battle cry, and may be roughly translated as “Be glorious!”

In 1162, the Papal Bull “Omne Datum Optimum” was issued by Pope Alexander III, which gave the Order of the Temple enormous potential power. It released them from all spiritual ties except to the Holy See itself, permitted them to have their own chaplains and special burial grounds in their own houses, freed them from paying tithes to the Church, and allowed them to collect their own tithes.

The Order also had an effective policy of recruitment. Service in the Order, which coupled adherence to strict monastic vows with the constant threat of mutilation or death on the battlefield, was considered adequate penance to compensate for any sin. Therefore, murderers, thieves, fornicators and even heretics were welcomed, provided they renounced their former ways and embraced the Order’s sacred vows. This policy may have infused the Order with freethinkers, and, in fact, a number of self-avowed penitent Cathar heretics (members of an ascetic, gnostic Christian sect which dominated southern France and northern Italy from about 1150 e.v.) were taken into the Order during the years of the atrocious Albigensian Crusade in southern France (1209-1250 e.v.).

The Order was composed of several classes: full brothers or knights, sergeants, chaplains, serving-brothers, and “clients.” The Order did not confer knighthood, only knights were admitted as full brothers.

At their initiation, which was held in secret, they swore the three basic monastic vows of chastity, poverty and obedience. The vow of poverty required the new knight to vest all his money and property in the Order.

They were vested with the habit of the Order (white for knights, black for sergeants, green for chaplains) and a sheepskin girdle or cord which they were never to remove, as a token of their vow of chastity. They were prohibited from bathing, and knights were prohibited from shaving their beards.

The Templars fought with the other Crusaders against Saladin during the Second Crusade, which failed. During their time in Palestine, many of the knights became fluent in Arabic, and there was undoubtedly a significant amount of discourse between the Templars and the Muslims. There has always been a great deal of speculation regarding the possibility that the Templar Order may have been influenced by the Assassins of Hasan ibn Sabah, due to certain similarities of organizational structure.

After Jerusalem was lost, the Templar headquarters was transferred to Paris and the Templars focussed their power in the West. They were principally concentrated in France and England, but owned extensive properties in Portugal, Castille, Leon, Scotland, Ireland, Germany, Italy and Sicily. When fully developed, they had over nine thousand preceptories, plus mills and markets. Many Templar preceptories and churches still exist. Templar churches are characterized by their circular shape.

Donation to the Templars was a popular form of charity, especially with the nobility. This income, coupled with the wealth of all its entering members, soon resulted in a substantial surplus of funds. At their height they were estimated to have an annual income of six million pounds sterling. This money was put to use providing what were essentially the first banking services in Europe.

Jacques de Molay was born into a noble family of Burgundy, and entered the Order of the Temple in 1265. He immediately proceeded to Palestine, where he distinguished himself in the war against the Muslims under the Grand Mastership of William de Beaujeu. He was unanimously elected Grand Master upon the death of Theobald Gaudinius in 1298.

In 1306, King Philip IV “the Fair” (Philippe le Bel) of France took refuge in the Templar headquarters in Paris to escape a civil commotion. Philip and the Knights had always been on good terms, and Philip had even chosen de Molay to be godfather to one of his children. Here he observed first hand the real wealth of the Order. Philip was bankrupt, and faced with severe governmental problems. He contrived a scheme to obtain control over the wealth and holdings of the Templars: they were to be accused of heresy and immorality.

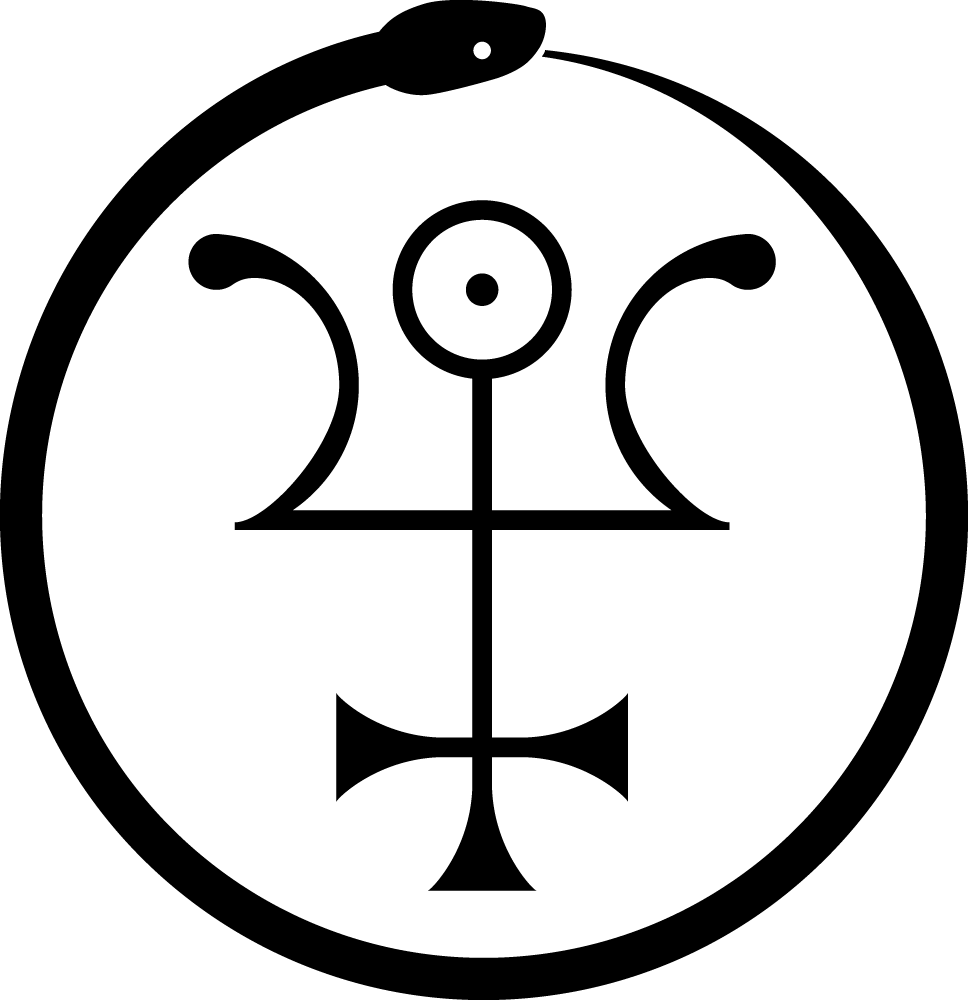

Pope Clement V, who had been enthroned through the assistance of Philip in 1305, invited the Grand Master of the Templars, Jacques de Molay, to Poitiers for a conference. In the mean time, two imprisoned ex-Templars were found, and offered their freedom if they would betray the Order. A number of charges against the Order were drawn up, including collusion with the Saracens; secret profession of paganism or Mohammedanism; requiring all novices to deny Christ, to trample and spit upon the Cross, and to bestow “obscene kisses” upon their prior; the tolerance and even encouragement of sodomy among the membership; and the secret adoration of an idol, mysteriously called Baphomet, which consisted of either a bearded head or an androgynous figure.

On Friday, October 13, 1307, e.v. Jacques de Molay and many of his brethren were arrested and thrown into prison. The king took possession of the Temple in Paris. The knights were tortured to extract confessions, and, not surprisingly, many confessions were obtained; most were contradictory. De Molay himself confessed under torture to doctrinal unorthodoxy.

De Molay was publicly sentenced on March 12, 1314. Asked to make his confession to the crowd, he stepped forward, but, instead of admitting guilt, he proclaimed his innocence and that of the Order, condemning himself to martyrdom. That evening, he was bound to a stake surrounded by combustible materials, and the torch of the executioners applied. With his last words, he invoked vengeance on Philip and Clement. Clement died the following month, and Philip died under mysterious circumstances the following November.

The Templar Order was formally suppressed in all the countries of Europe except Scotland.

References:

Crowley, Aleister; The Heart of the Master [Ordo Templi Orientis, 1938], New Falcon Publications, Scottsdale, Arizona 1992

Goodrich, Norma Lorre; The Holy Grail, Harper Collins, New York 1992

Howarth, Stephen; The Knights Templar, Dorset Press, NY 1982

Mackenzie, Kenneth; The Royal Masonic Cyclopaedia [1877], Aquarian Press, Wellingborough 1987

Mackey, Albert G.; Encyclopedia of Freemasonry, Masonic History Co., NY 1909

Robinson, John J.; Born in Blood, the Lost Secrets of Freemasonry, M. Evans & Co., NY 1989

Rudolph, Kurt; Gnosis, Harper & Rowe, San Francisco, 1977

Original Publication Date: 5/24/95

Originally published in Red Flame No. 2 – Mystery of Mystery: A Primer of Thelemic Ecclesiastical Gnosticism by Tau Apiryon and Helena; Berkeley, CA 1995 e.v.