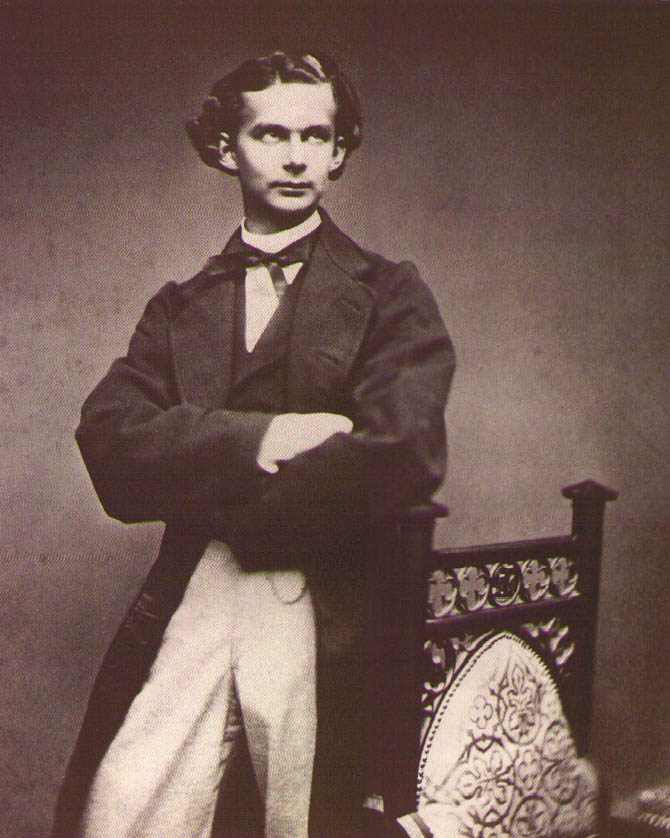

(1845-1886 e.v.)

by T. Apiryon

Ludwig II, the reclusive “Swan King,” also known as the “Mad King” of Bavaria (1864-1886). Ludwig was the last of the German feudal princes: a romantic dreamer who viewed himself as a divinely sanctioned monarch after the model of his hero, Louis XIV, the “Sun King” of France. He was a great patron of the arts, especially of painting, music, sculpture, literature and architecture. He is now most well known for the three lavish palaces he built: Schloss Linderhof near Oberammergau, which boasts a “Grotto of Venus” complete with concrete stalactites and an indoor lake with a boat shaped like a cockleshell; Schloss Herrenchiemsee, a miniature replica of Versailles on an island in the Chiemsee; and Schloss Neuschwanstein, a fairy-tale castle with soaring turrets built atop a mountain crag near Füssen, on the Austrian border.

Ludwig was a passionate devotee of Richard Wagner, and his greatest patron. Wagner’s Festspielhaus in Bayreuth was largely funded by Ludwig, and Ludwig’s aid was unquestionably a major factor in Wagner’s success and tremendous influence in history. Because he detested being ogled by the “plebians,” Ludwig often arranged for private performances of Wagner’s operas where he was the only person in the audience.

Ludwig’s “leitmotif” was the swan of Lohengrin. Swans were to be found embroidered on his cushions, painted on his china, carved on his furniture, and swimming in his pools. Neuschwanstein is provided with swan tapestries, door knobs and faucets.

Wagner referred to Ludwig as “Parsifal,” and indeed, Ludwig seems to have fancied himself to be the Graal King, one of a chain of rulers who knew the inner mysteries of Christianity and their pre-Christian origins, and who drew power therefrom. Ludwig intended his most famous castle, Neuschwanstein, to represent Montsalvat. It contains a room called the “Singer’s Hall,” which is designed as a Graal Temple, with murals depicting scenes from the Eschenbach version of “Parzival.” Neuschwanstein also contains a pillar intended to represent the “World-Ash” tree of Germanic mythology.

Later in his life, Ludwig experienced a number of crushing blows. He was forced by Bismarck to join the German Empire under William I of Prussia. He and Wagner had a falling out, and his plans for marriage failed.

He withdrew into increasing isolation and seclusion, and his behavior became increasingly eccentric. He began to dine with busts of Louis XVI and Marie-Antoinette rather than his friends. He suffered from insomnia, and would go for long sleigh-rides with his attendants in the middle of the night. There was a particular tree on his grounds which he considered to be sacred. Whenever the sleigh approached this tree, he would call to the driver to stop the sleigh. He would then get out of the sleigh, bow to the tree, then get back into the sleigh and continue on his way. Rumors of his homosexuality began to spread. To compound matters, his expensive avocations had placed him into severe debt.

In 1886, his ministers, along with his uncle and successor, Luitpold, resolved to depose him. They had him examined by Dr. Bernard von Gudden, who declared him to be insane, even though another psychiatrist had declared him to be perfectly sane only a few weeks before. He was taken into custody by the authorities only days after he had occupied the recently completed Neuschwanstein, and confined to Schloss Berg on the eastern shore of the Starnberger See near Munich, under Dr. von Gudden’s care. A few days later, he and Dr. von Gudden were found drowned in the lake. Precisely how he and Dr. von Gudden came to be drowned in the lake is unknown to this day, though there has been an abundance of speculation. Schloss Berg is now a resort hotel, and a cross in the lake marks the location of Ludwig’s death.

References:

Chapman-Huston, Maj. Desmond; Ludwig II: The Mad King of Bavaria, Dorset Press 1990

McIntosh, Christopher; The Swan King, Allen Lane, London 1982

Grunfeld, Frederic V.; The Princes of Germany, Stonehenge Press, Chicago 1983

Sabor, Rudolph; The Real Wagner, Cardinal/Sphere/Penguin, London 1987

Original Publication Date: 1995

Update: 2/1/97

Originally published in Red Flame No. 2 – Mystery of Mystery: A Primer of Thelemic Ecclesiastical Gnosticism by Tau Apiryon and Helena; Berkeley, CA 1995 e.v.