The Role and Function of Thelemic Clergy in Ecclesia Gnostica Catholica

by Tau Apiryon

The Christian Apostolic Succession

The term “apostolic succession” derives from the Christian tradition that Jesus bestowed particular powers upon his apostles, which they were able to pass on to their successors. While still alive, He gave Peter the “keys of the kingdom of heaven” and the power to “bind” and to “loose” in heaven as on earth (Matthew XVI:18-19). At the ressurection, He bestowed the power to remit and retain sins upon the assembled apostles by breathing upon them and saying “Receive ye the Holy Ghost” (John XX:22-23).

The precise formula for conferral of the apostolic succession in the Episcopate was established later. The essentials are the invocation of the Holy Spirit and the laying on of hands (cheirotonia), with right intent, after due preparation (i.e., after Christian baptism, confirmation and ordination to the Priesthood). The rite of exsufflation, or breathing upon the recipient, is also considered an integral component of the rite by some denominations. The apostolic succession is embodied in the Episcopate of the Catholic, Anglican and Orthodox Churches, as well as within the “wandering bishops” tradition, which includes the French Gnostic Churches. According to Saint Augustine, the powers conferred by a validly transmitted apostolic succession (i.e., the powers to remit and retain sins and to transmit the Holy Ghost) cannot be taken away once conferred; even though the individual may loose his standing, recognition and authority within the Church.

Even though the apostolic succession is embodied in the Episcopate, the fact that one holds a validly transmitted apostolic succession does not automatically make one a bishop within any particular church. Episcopal power is derived from the apostolic succession, but Episcopal authority is delegated by the leadership of the Church. The ordination or “consecration” of a bishop may involve a perfectly “valid” conferral of the apostolic succession, but if it was performed without the authorization of the Church leadership, it is “illicit,” and conveys no authority in the Church.

Within the exoteric Christian community, the apostolic succession is considered to emanate from Jesus and the apostles. However, from a historical and anthropological perspective, its roots are much deeper. The Book of Hebrews (V, VI, and VII) describes how Jesus was made a “Priest for ever after the Order of Melchizedek” by God (in accordance with Psalm 110), and how this eternal Order of Priesthood was the foundation of the spiritual authority of the apostles. The apostolic succession may then be considered to constitute the Order of Melchizedekian Priesthood. Who was Melchizedek? According to the sect of Melchizedekian Gnostics, he was an Avatar of Seth, the third son of Adam. According to cultural anthropologists, he was probably an ancient Jebusite Priest-King of the polytheistic Canaanite religion, which, being transplanted from Mesopotamia, had its deepest roots in ancient Sumeria. Qabalistically, Melchizedek, King of Salem, is the King of Righteousness and Peace, i.e. Jupiter/Chesed.

In addition, as the heir to the patriarchal Hebrew tradition, the apostolic succession of Jesus would naturally have included the spiritual succession of Moses– who was, of course, an Egyptian initiate.

Later, the apostolic succession acquired a series of additional spiritual successions through its relationship with Roman paganism. The early Roman ruler Numa Pompilius (716-673 p.e.v.) founded the College of Pontiffs to govern the pagan religious system of Rome. The president of this college was known as the Pontifex Maximus, “Supreme Pontiff.” On his accession as Emperor, Octavian Augustus took this title for himself, and it was thereafter reserved for the Emperor as formal head of the State Religion. After the time of Christ, the idea of monotheism became more popular. The Emperor Elagabalus (218-222 e.v.) established the solar Baal worship of his native Syria as the imperial cult within the Roman pagan milieu. The cult of Elagabalus was short lived, but the main feature, the henotheistic idea of all the diverse gods subordinate to a supreme solar Deity, was resurrected by the Emperor Aurelian (270-274 e.v.) and merged with the Mithraic religion as the imperial cult of the Deus Sol Invictus. Under this system, the Emperor was considered the vicegerent of the supreme god Sol Invictus, who was also known by the names Mithra and Oriens. The Sol Invictus cult was very syncretistic, and incorporated elements of most of the various religions of the Roman Empire of the time, including Christianity. The system of Christianity was, in fact, very compatible with the system of Sol Invictus. There is a third century vault mosaic in the tomb of the Julii under St. Peter’s which depicts Christ as Sol, rising in his chariot.

The Sol Invictus cult continued to grow under Aurelian’s successors and reached its pinnacle of success under the Emperor Constantine I “the Great” (Emp. 310-337 e.v.). Constantine retained the title of Pontifex Maximus throughout his life, even through his death-bed baptism as a Christian. The Emperor Gratian (Emp. 367-383 e.v.), however, was converted relatively early in his life by St. Ambrose, and renounced the title of Pontifex Maximus in 379 e.v. There is no record, at least no record available to the public, of Gratian having appointed a successor to the office of Pontifex Maximus. However, though he renounced leadership of the state church hierarchy, he did not dissolve it; and that same year, the Bishop of Rome, Damasus I (Papacy 366-384 e.v.), referred to himself as the Pontifex Maximus in a petition to the Emperor for judicial immunity.

Damasus was a powerful and ambitious leader. He had won the office of the Roman Episcopate by armed force, and he presided over a notoriously corrupt and sensuous church. He was a suave intellectual who moved easily among the pagan elites of Rome and converted many of them to Christianity. He was also the first of the Bishops of Rome to assert Roman primacy over all other bishops, and, as such, was the first true “pope.” Appointment, even clandestine appointment, as supreme head of the Roman State Church, which was ripe for Christian conversion, would have suited his purposes very well.

On his baptism in 380 e.v., Gratian’s successor Theodosius I “the Great” (Emp. of East 378-394, Emp. of East and West 394-395 e.v.) proclaimed the Christianity of Pope Damasus the official State Religion of the Roman Empire. He then proceeded to issue a number of edicts which rendered the practice of pagan religions illegal. Pope Leo I “the Great” (Papacy 440-461 e.v.) publicly claimed the title of Pontifex Maximus for himself. Finally, under the Papacy of Paul II (1464-1471 e.v.), the title was made an official designation of the office of pope.

Authors such as Ragon, Hislop, Inman, Higgins and Forlong have pointed out in detail the conspicuous similarities between the rites and symbols of Roman Catholic Christianity and those of its Roman predecessors, including the substitution of Saints for Gods, the replacement of the College of Pontiffs with the College of Cardinals, the replacement of the Pontifex Maximus with the Pope, and the celebration of Christ’s birthday on December 25, the birthday of Sol Invictus Mithra. We may never know whether Pope Damasus I was actually appointed Pontifex Maximus of the Roman Church. Nonetheless, that mantle fell squarely upon his shoulders and those of his successors. Having either actually or effectively absorbed the Sol Invictus cult, the apostolic succession of the Roman Catholic Church has, since the time of Damasus, conveyed the spiritual successions of nearly all of the pre-Christian pagan/solar faiths of the Roman Empire.

Thus, the “apostolic” succession, though considered within the exoteric Christian community to begin and end with Jesus, actually embodies the spiritual successions of the entire Western religious heritage: Christian, Judaic, and Pagan.

The Thelemic/Gnostic Succession

As Thelemites, we are little concerned with the exoteric Christian interpretation of apostolic succession. The power to remit and retain sins, which is the entire point of the Christian apostolic succession, is not particularly relevant to Thelemites. Therefore, it is not of critical importance for a bishop of the Thelemic E.G.C. to hold a valid “apostolic succession” as defined by the Canon Law of exoteric Christianity. The spiritual succession we hold from the Master Therion, the Prophet of the Aeon, the founder of our religion, is of much greater significance to us. This Thelemic/Gnostic succession, embodied in the leadership of O.T.O., conveys the power and authority to administer the outer institutions of the Thelemic Religion: the O.T.O. and Gnostic Catholic Church.

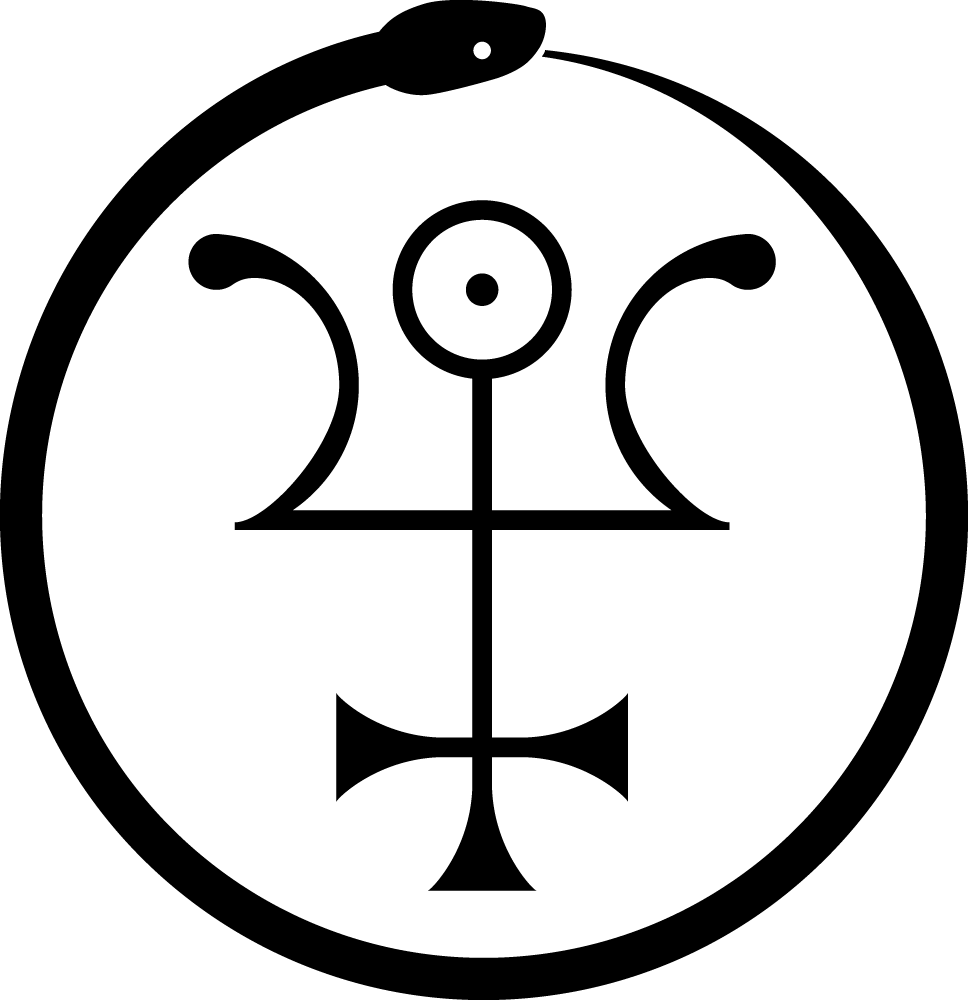

Just as the Christian apostolic succession, which nominally begins with Jesus, actually conveys the spiritual heritage of many earlier traditions, so does our Thelemic/Gnostic succession from the Master Therion convey all the various lineal successions of the “constituent originating assemblies of the O.T.O.” listed in Book 52, which were conferred upon Crowley by Theodor Reuss when Crowley was made head of O.T.O. for Ireland, Iona and all the Britains. One of these constituent originating assemblies was the Gnostic Catholic Church, which was originally Christian, and whose Episcopate conveyed the traditional apostolic succession through Joseph René Vilatte, one of the “wandering bishops.” Thus, our Thelemic Ecclesia Gnostica Catholica has united virtually all of the various spiritual successions of the Western religious tradition in service to the Law of Thelema.

The Thelemic/Gnostic succession embodied in the Episcopate of our Gnostic Catholic Church can be considered, in both a symbolic and a spiritual sense, as a heritage of the primitive Order of Priesthood, as a transmission of the Essence of all the “saints of the true church of old time,” whose mingled Blood fills the Cup of Babalon. Upon this succession we may rightfully claim the heirship, communion and benediction of those saints. Through the right use of this succession we may build the invisible edifice of a Spiritual Ecclesia as we celebrate our Gnostic Mass; and by the power of this succession we may once again awaken the egregore of the True Church of Old Time upon the Earth.

Priesthood and Gnosis

One of the most commonly cited “invariants” of Gnosticism is the doctrine of personal illumination: that the salvific Gnosis is obtained directly from the transcendent realm by each individual Gnostic. Some modern writers have gone so far as to opine that the violent opposition of the early Catholic Church against the Gnostics was a result of the refusal of the Gnostics to accept the concept of a mediatory priesthood. There were, of course, many other reasons beside this; but this idea has led some to question the value of an ecclesiastical hierarchy in the E.G.C.

First, it should be pointed out that many classical Gnostic systems had ecclesiastical hierarchies. Most of the Alexandrian and Syrian Gnostic groups were centered around an authoritative Teacher and his deputies. The Manichaean Church had an elaborate and very rigid hierarchical system composed of lay members (Hearers) and a clergy (Elect), who were governed by 360 Elders, 72 Bishops, 12 Masters and a single Archegos or chief.

Second, while many of us tend to view the “Gnosis” as a true unitive experience, like Samadhi, or the “Enlightenment” of Zen Buddhism, or the Knowledge and Conversation of the Holy Guardian Angel, many of the Classical Gnostic systems viewed it simply as the personal conviction that one’s own true nature was divine, and, as such, that one dwelt in the material world as a “stranger in a strange land,” as a traveler whose ultimate goal was the transcendent Pleroma. This belief could only bring “salvation” if it were truly a deep knowledge as opposed to a purely intellectual belief. It required the strength of what William James called the “conversion experience.” A Gnostic clergy would have been useful to those in pursuit of this experience: as sources of theoretical and technical information, of spiritual guidance and reassurance; to answer their questions, resolve their doubts and help them through their studies and meditations to come ultimately to the full personal realization of the Gnosis.

The real distinction between the clergy of the Gnostic and Catholic Christian systems was that the Catholic priest actually took the part of Christ in intervening on behalf of the individual; whereas in the Gnostic Christian systems, the clergy assisted the individual toward accomplishing this for him or herself.

The two systems had similarly divergent doctrines on the nature of Christ. The Catholics held, and hold, him to be the effecter of World Salvation through the principle of vicarious sacrifice; the Gnostics held him to be a divine Illuminator, pointing the way toward salvation for those with the ability to see.

Function of the E.G.C. Clergy

In the E.G.C., as in the Christian Gnostic systems, personal Gnosis is stressed, so our clergy do not serve as intervening spiritually on behalf of the congregation. Although they may, if they have the ability, serve somewhat in the same capacity as the Classical Gnostic clergy, i.e. as teachers, facilitators and counselors, the principal duty of the E.G.C. clergy is to see that the rituals are “rightly performed with joy & beauty.” As such, they are the official representatives of the Church and the custodians of its paradigms; they are responsible for communicating the Word of the Thelemic E.G.C. to the world.

In the Roman Catholic Church, there is no such thing as an incompetent priest in celebrating Mass. If he is duly ordained and says the words, the miracle is alleged to occur. It does not matter if he mumbles his lines with his face buried in the Missal, wears his chasuble backwards and forgets to ring the bell.

Such is not the case in the E.G.C. Where the Catholic Mass is a miraculous rite, depending for its efficacy on the Grace of God; the Gnostic Mass is a magical rite, depending for its efficacy on the knowledge, power and talent of the celebrants. The effectiveness of the rite is directly proportional to the magical skill of the officers. The officers must, then, be magicians: they are technicians performing a complex technical procedure. They must, therefore, be educated in its theory and trained in its practice to be effective.

The E.G.C. clergy also serve a dramatic function as performers in a mystery play, whether they are presiding over the Gnostic Mass, or a baptism, or a wedding, or any other sacred rite. Their roles are those of specific divine forces which are interior elements of each individual as well as forces of nature. As such, their function is to create a sympathetic magical response in the consciousness of those present. The effectiveness of this function is directly proportional to the dramatic ability of the officers.

Another aspect of the function of the E.G.C. clergy is social leadership. One of the basic functions of any religion is to define a community; and churches have always served the communal aspects of religion. The clergy of a church, whatever their other duties may be, must work to promote a sense of community and friendship among the members of the church. While the initiatory rites of M:.M:.M:. and O.T.O. are restricted to the members of certain degrees, the Gnostic Mass and most of the other rites of E.G.C. are open to all members, and in some cases, even to non-members. The E.G.C. thus serves as the social focal point of the Thelemic community, and its clergy are responsible for fostering harmony and fellowship.

In summary, the clergy of E.G.C. must be thoroughly familiar with the official ceremony of the Gnostic Mass and must have a good general understanding of its theory. They must have a relatively clear conception of the basic doctrines of Thelema in general and of the O.T.O. and E.G.C. in particular (in accordance, of course, with their degree of initiation). They should be familiar with the theory and techniques of ceremonial Magick and group dramatic ritual in particular. Ideally, they should also have a certain amount of aptitude for dramatic performance: they should be understand teamwork, they should “look good in robes,” as Crowley put it, and they should be able to draw and hold the attention of those attending the ritual. They should, as visible leaders, be able to offer their services as facilitators to their congregations, in the form of teaching and counseling. They should endeavour to create and maintain a sense of community within the congregation. They should understand the differences, as well as the similarities, between their roles as Thelemic clergy and those of the clergy of other religions. Finally, they should establish their link with the egregore of the church through initiation, ordination and regular celebration of the Gnostic Mass.

References:

- Eliade, Mircea (Editor in Chief); The Encyclopedia of Religion, MacMillan Publishing Co., New York 1987

- Forlong, J.G.R.; Faiths of Man, a Cyclopaedia of Religions [Bernard Quaritch, 1906], University Books, NY 1964

- Forlong, J.G.R.; Rivers of Life, London 1883

- Higgins, Godfrey; Anacalypsis, an Attempt to Draw Aside the Veil of the Saitic Isis; or, an Inquiry into the Origin of Languages, Nations, and Religions. Longman, Green, et al., London 1836, reprinted by Health Research, Mokelumne Hill, CA 1972

- Halsberghe, Gaston H.; The Cult of Sol Invictus, E.J. Brill, Leiden 1972

- Hislop, Rev. Alexander; The Two Babylons, or, The Papal Worship, Loizeaux Bros., New Jersey 1916, 1959

- Inman, Thomas; Ancient Pagan and Modern Christian Symbolism [1869/1874], Kessinger Publications, Kila, MT 1993

- James, E.O.; The Nature and Function of Priesthood, Barns & Noble, New York, 1955

- Le Forestier, René; L’Occultisme en France aux XIXème et XXème siècles: L’Église Gnostique, Ouvrage inédit publié par Antoine Faivre, Archè, Milano 1990

- McDonald, William J. (Ed. in Chief); New Catholic Encyclopedia, McGraw Hill, NY 1967

- Rudolph, Kurt; Gnosis, Harper & Rowe, San Francisco, 1977

- Weltin, E.G.; The Ancient Popes, The Newman Press, Westminster, MD 1964

Original Publication Date: 1997