The Sacramental System of Ecclesia Gnostica Catholica

by Tau Apiryon

Introduction

The word “church” derives ultimately from the Greek Doma Kyriakon, meaning “House of God.” It is the physical structure of a place of communal worship as well as the religious community itself and the institutions established to serve that community. The purpose of such institutions is to bring the words “religious” (or “spiritual”) and “community” together: to bring spirituality into the community; and to bring community into spirituality. The church must provide general access to the teachings and experience of a particular religion; must establish and maintain the relevance of the religion within the daily lives of the members of the religious community; and must foster a sense of communion, both among the members of the community, and between the earthly community and the divine community. The specific religious rites used by a church to in the activation, maintenance, and nurturing of the spiritual community are called sacraments.

The regular performance of a single sacramental ritual, even if that ritual is of surpassing excellence and its celebration results in great benefits, is not sufficient to accomplish all the purposes of a church. The Gnostic Catholic Church must provide more than the regular performance of the Gnostic Mass, and in the final paragraphs of Liber XV itself, we find reference to such rites as baptism, confirmation at puberty, weddings, and ordination. Section 9.05(B) of the O.T.O. Bylaws reflects the use of Liber 106 in performance of last rites by E.G.C. clergy. These, along with the eucharistic service of the Gnostic Mass itself, constitute six of the seven traditional “sacraments” of the Roman Catholic Church. Crowley evidently intended for his successors to organize, as part of an overall program for creating a Thelemic society, a Thelemic ecclesiastical system with a variety of sacramental rites, which achieve the goals of a Thelemic Church by providing a religious and social context for the fraternal, initiatory and magical work of O.T.O. and A:. A:.

It may at first appear strange that Crowley would have adopted a seemingly “Old Aeon” sacramental system for promulgation of a “New Aeon” religion. However, as demonstrated by the structure and content of of Liber XV, the process is not one of simple “adoption,” but of adaptation; not of “borrowing” but of learning. While the overlay of doctrine may change from culture to culture, and Aeon to Aeon, many of the technical tools used by various religious systems are of universal applicability, because they deal with basic factors of human psychology and consciousness which are essentially scientific in nature. The Hebrew Qabalah, the Enochian system of Dee and Kelly, the Sacred Magic of Abramelin the Mage, the Goetia, and the system of the O.T.O. are examples of magico-religious systems whose technical principles bridge the gap between doctrines, theologies and Aeons.

While the system of the seven sacraments may be used by the Roman Catholic Church to promulgate its particular doctrines, the technical principles of this system are far older than Christianity and of far broader applicability. The Roman Catholic Church was built on the ruins of syncretistic Roman paganism. Most, if not all, of the sacramental principles adopted by the Catholic Church have their deepest roots in Egyptian, Babylonian and Greek pagan practice. The Christians found the structural and technical tools used by previous religious systems to be useful for promulgating their own message, and adapted them to their own particular use. Such tools constitute the elements of an ancient science of sacerdotalism, based on theorems rooted in the deepest psychological and spiritual needs of humanity, and reflected in the teachings and rites of the various constituent assemblies of the Western Esoteric Tradition. This sacerdotal science is one of the jewels in the scepter which, once held by Osiris as the Hierophant of past times, must now be taken up and raised by Horus as he ascends to the Throne of his predecessor.

The purpose of this essay is to examine the nature and fundamental principles of this sacerdotal science, and to evaluate its applicability within the Thelemic Ecclesia Gnostica Catholica.

Religion, the Sacred, and Sacrament

The word “religion” is from the Latin word religio, meaning observant or heedful. The word religio may be derived from the roots re, again, and ligo to bind; meaning to re-bind or re-establish a severed connection. The word “sacred” comes from the Latin sacer, meaning devoted or dedicated, especially to a particular deity. Thus both words refer to the creation of a bond or a link between the worshipper and the object of worship. The Latin word sacramentum, from which we derive our word “sacrament,” is derived from the root sacer and refers to that which makes something sacred, i.e. that which creates a devotional or dedicational bond or link. The usual ecclesiastical definition of sacrament is “an outward sign of an inward grace,” or, as Saint Augustine put it, “a visible sign of a thing divine,” i.e., a natural phenomenon possessing a supernatural significance. The actual usage of the word sacramentum in the Latin language carried the meaning “that which binds or obliges a person,” and it referred to military oaths and legal processes as well as to religious obligations. The oath of loyalty taken in each degree of the Mithraic Mysteries, for example, was referred to as a sacramentum. The sacraments of a religion are thus the means whereby atonement or reconciliation with Divine Law is achieved, and a bond, agreement or covenant is established between the outer and the inner, the human and the divine; they constitute, in essence, a system of yoga.

The Christian Theory of the Sacraments

In the Christian tradition, the priesthood has always been defined by its responsibility to effect the reconciliation between the people and God as the successors to Christ’s apostles, who received his charge and power to act on his behalf. This idea gradually developed under the influence of Neoplatonism into a liturgy of seven sacraments (or “mysteries,” as they are known in the Orthodox Church), which are: baptism, confirmation, penance, the Eucharist, holy matrimony, holy orders and extreme unction. The Roman Catholic Church has many sacred rites which are not held to be sacraments per se, such as exorcism, the consecration of holy chrism, etc. These rites are termed “sacramentals.”

The traditional Christian view of the theory of the seven sacraments is that they mediate and effect the atonement of the individual soul with the Godhead through the operations of purification (expiation of sin) and sanctification (instillation of virtue), thus rendering the individual fit for the reception of Divine Grace which brings salvation. The Priesthood serves as the “third party” which mediates and administers the covenant between the members of the Church and the Godhead. In this capacity, they and the sacraments themselves are identified with Christ, the mediatorial aspect of the Godhead. Note that prayer, while certainly dealing with the relationship between humanity and Divinity, is not considered a sacrament in the ecclesiastical context because: (1) Catholic Christians do not pray directly to God, but to saints for intervention on their behalf; and (2) prayer is not administered by the priesthood, and is thus not a function of the Church per se. The administration of the Seven Sacraments is, without doubt, the principal function of the Catholic Church; and, as we have seen, any church can be defined as an institution established to administer a system of sacraments appropriate to the religion it represents.

The Number of the Sacraments

The number of the sacraments in the primitive Christian Church is difficult to ascertain, because a sacramental doctrine had yet to be established; but it was certainly less than seven. The rite of baptism was originally considered to expiate all sins, past and future; so no sacrament of penance was considered necessary. The laying on of hands which now constitutes the central rite of confirmation was originally conferred as part of the baptismal rite. The rites of baptism and the Eucharist were administered by bishops, who were elected by the congregation and had received the Apostolic Succession. The bishops were assisted by “presbyters” (elders) and “deacons” (servants, or ministers). The Order of Priesthood was instituted later, along with the minor orders, as a development of the Presbyterate. The word “priest” is ultimately derived from the Greek word presbyteros, “elder.”

The doctrine of the sacraments was not fully developed until the middle ages. There were originally only two actual sacraments: baptism and the Eucharist, although the functions of the Church were numerous. Dionysius the Areopagite recognized six Sacraments, Abelard and Hugo of St. Victor recognized five, Bernard of Clairvaux recognized ten. Peter Lombard fixed the number at seven, a number which was affirmed by the Council of Trent in the mid-16th century.

Most Protestant churches, based on a strict reading of New Testament scripture, recognize only two sacraments: baptism and communion. Some of the Christian Gnostic systems also recognized fewer than seven sacraments. This is primarily because the Christian theory of the sacraments includes the assumption that incarnation and generation are tainted with original sin– which, to use Gnostic terminology, refers to the Mixture and concealment of the Light of Spirit within the Darkness of Matter. Some anticosmic Gnostic sects considered matter as being entirely valueless and unredeemable, thus they saw no virtue in baptizing with water or in sanctioning sinful activities such as sex. For example, the Cathar Church recognized only one Sacrament, called the Consolamentum, in which the Holy Spirit was received and the material life renounced. The Consolamentum combined aspects of baptism, confirmation and holy orders, and those who had received the Consolamentum were considered “Perfect.” Sinful acts committed after reception of the Consolamentum were not redeemable except by voluntary self-martyrdom.

Jules Doinel’s Église Gnostique (1890), which incorporated some Cathar doctrines, recognized two sacraments, the Consolamentum and the Appareilamentum, corresponding to baptism/confirmation and penance, respectively. Jean Bricaud’s Église Gnostique Universelle (1907), a schismatic branch of Doinel’s church, recognized five sacraments. Matrimony was not considered sacramental, and penance was considered a non-sacramental prerequisite for the other sacraments.

In contrast with the anticosmic Gnostic doctrine, the Catholic and Orthodox churches hold that incarnation and generation can be redeemed by the Grace of God, which may be secured through the covenant of the sacraments. Thus, the Catholic Church was able to develop, under the influence of Neoplatonist philosophy, a complete system of seven sacraments, corresponding to the interaction of the Holy Trinity (3) with the Created World (4). The Seven Sacraments may, therefore, be divided into two subdivisions: the four “natural” sacraments of baptism, confirmation, holy matrimony and extreme unction correspond to the four life stages of birth, puberty, marriage and death; and the three “elective” sacraments of holy orders, penance and the Eucharist relate to the transcendence of the natural world into that of the Spirit.

The Traditional Significance of the Seven Sacraments

The Christian sacrament of baptism effects the first prerequisite for salvation– regeneration: the second birth which purifies the body and the soul by the expiation of “original sin”– that is, sin which is inherent in physical incarnation. The child is received into the Church, outside of which there is “no salvation.” Baptism comes from the Greek word baptizô, which means to bathe or immerse. The rite of baptism is far from being unique to Christianity. It was practiced by the ancient Egyptians, Etruscans, Israelites, Samaritans and Magi, the Zoroastrians, and the Manichaeans; and in the Eleusinian, Isiac and Mithraic Mysteries. It is still practiced by such decidedly non-Christian sects as the Mandaeans. Its primitive, essential significance is as a sacramental rebirth into a new life and washing away of the traces of the old life; as such, it corresponds to the beginnings of the yoga practice of Yama.

The Christian sacrament of confirmation effects the second prerequisite for salvation: belief in salvation. Whereas baptism is essentially passive, confirmation is active. The confirmand makes a conscious and voluntary profession of faith. He or she then receives the Holy Ghost (the Third Person of the Trinity) through the laying on of hands by the bishop. The word confirmation is from Latin roots which mean to “join firmly.” The rite of confirmation is paralleled in other faiths by the various rites of passage performed at puberty, and represents an awakening into a new awareness of reality. The fundamental sacramental significance of this rite is the alignment of the individual, conscious will with the Divine Will, expressed as an acceptance of the essential tenets of the faith. As the active, voluntary aspect of initiation it corresponds to the beginnings of the yoga practice of Niyama.

The Christian sacrament of penance deals with the continuing struggle against sin after baptism, through confession, contrition and absolution. The word penance is from the Latin word paenitentia, meaning “a regretting.” Penitential and purificatory ascetism was common to many ancient faiths, especially the Eastern religions of Mesopotamia, India and Persia. The purificatory “negative confession” was an essential rite in Egyptian magical ritual. The essential sacramental significance of this rite is the continual renewal of the Divine Covenant through self-awareness and self-discipline.

The Christian sacrament of the Eucharist effects the direct communion of the individual with the Godhead through the person of Christ (the Second Person of the Trinity). The people offer Christ as a vicarious sacrifice of themselves to God, and God returns the life-giving Substance of Christ to the people, through the principle of do-ut-des, “I give that thou mayest give.” The word Eucharist is from the Greek wordeucharistos, meaning thanksgiving, which in turn can be derived from the Greek roots eu + charismata = “good gifts” or “good graces.” The ceremony of the Eucharist derives from the sacrificial rites of the ancients. The eucharistic sacrifice of bread and wine was practiced in the Orphic and Mithraic Mysteries.

The Christian sacrament of holy matrimony deals with the purification and sanctification of generation through the exchange of devotional vows, recapitulating the covenant between God and Man as a covenant between Man and Woman. The word matrimony is from the Latin word for “motherhood.” The rite of marriage is nearly universal in human culture, and its origins are lost in antiquity.

The Christian sacrament of holy orders deals further with the sanctification of confirmation through the renunciation of material life for a life dedicated entirely to the service of the Church as an agent of God, an apostle and vehicle of Christ, and a conduit for the Holy Ghost. The word ordination is from the Latin ordinare, meaning to “order, arrange or appoint.” Nearly all of Humanity’s religions have rites of ordination for those who enter into the path of service.

The Christian sacrament of extreme unction, which, together with the viaticum is also known as “last rites,” deals with the final preparation of the soul for death, in order to ensure the salvation of the soul and its readiness to enter the Kingdom of Heaven. Final purification is effected by the absolution of remaining sins and by assisting the individual to let go of all his or her worldly attachments and concerns. Final sanctification is effected by a recapitulation of the profession of faith. The priest then assists the individual to establish a final atonement with the Godhead through prayer. The word unction is Latin for “anointing,” i.e. the application of ointment or salve; thus both “soothing” and “salvation.” The word “extreme” refers to the sacrament being carried out just before death, at the “extremity” of life. The termviaticum is a Latin term meaning “provisions for a journey,” as for a soldier going off to battle; and it refers specifically to the final administration of the Eucharist. One of the essential criteria of a religion is that it must deal, in some way, with the disposition of the individual soul, consciousness or ego after the death of the individual’s body. Most sacramental religions, therefore, offer some sort of last rites to provide comfort and support to the individual prior to his or her passage into whatever lies beyond. In the ancient Egyptian religion, last rites served to ensure that the dying person had the knowledge and provisions necessary to make a successful passage through the tests, ordeals and obstacles which he or she would encounter on the way to the Blessed Abode.

The Esoteric Significance of the Seven Sacraments

The three elective sacraments correspond to the three alchemical principles of Salt, Sulfur and Mercury; and the four natural Sacraments correspond to the four alchemical elements of air, fire, water and earth.

The seven sacraments also correspond to the seven ancient planets. Baptism by water is attributed to Luna; the confirmation of consciousness to Mercury; holy matrimony to Venus; holy orders, establishing a mediatory priesthood, to Sol; penance, the war against sin, to Mars; the Eucharist, the Royal Sacrifice and Thanksgiving for Good Graces, to Jupiter; and extreme unction at death to Saturn.

The planets are in an intermediate position between the celestial and terrestrial spheres, and are thus well suited to symbolically fulfill the role of mediators between Heaven and Earth. Qabalistically, they represent the seven rays or vessels of emanation. They also represent the seven deadly sins and the seven virtues; the seven bonds of brotherhood; and the numerous “sevens” of the Apocalypse: the seven hills of Babylon; the seven cities in Asia; the seven seals of the Book; the seven heads of the Beast and the seven eyes and horns of the Lamb; etc.

On the Tree of Life in Assiah, the four natural sacraments (baptism, confirmation, matrimony and last rites) occupy the spheres of Yesod, Hod and Netzach, and the Path of Tav. This is the First Order, the Magical Triangle, the Man of Earth Triad, the realm below the Veil of Paroketh.

The three elective Sacraments (orders, penance and the Eucharist) occupy the spheres of Tiphareth, Geburah and Chesed. This is the Second Order, the Ethical Triangle, the Lover Triad, the realm of the Adepts.

The Third Order, Supernal Triangle, Hermit Triad and Realm of Masters has but one of the seven qabalistic planets, Saturn: which is also expressed in the lowest Path, that of Tav. The Sacrament of last rites deals with the separation of Spirit and matter. Spirit goes on into the realm beyond life (the supernals)– matter returns to Earth (Tav).

Thus, the seven sacraments can be viewed as representing the harmonizing of various aspects of the natural and voluntary life of the individual with the Will of God, or True Will, through the operational modes of the seven planets.

The Sacraments in the Thelemic E.G.C.

We read in Book 837, “The Law of Liberty,” that “every act must be a ritual, an act of worship, a Sacrament.” This is a requisite task for the Adept, who must ultimately be his own priest. However, it is the function of the institutions of Thelema, such as M.M.M. and E.G.C., to convey their doctrines and mysteries in sacramental form. The obligation of each degree of M.M.M. is truly a sacramentum in the original sense of the word; and the E.G.C., being a church, is, by our definition, an institution established to administer a system of sacraments. The sevenfold system of sacraments is the only such system which is both practicable and conformable to a comprehensive magical theeory based on qabalistic principles.

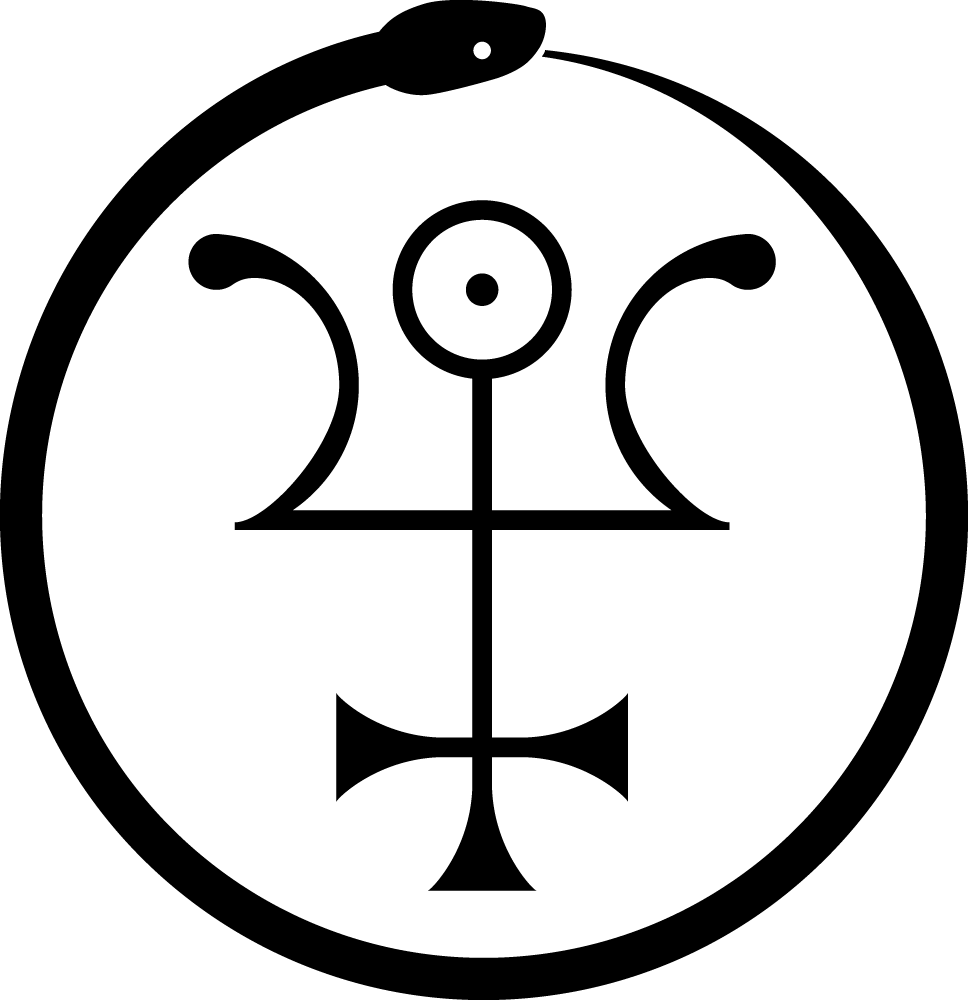

While the E.G.C. is Gnostic in that it derives historically from Jean Bricaud’s Église Gnostique Universelle, and it holds to the doctrines of emanation and of redemption through Gnosis or illumination; it has accepted the Law of Thelema, and so rejects the anticosmic doctrine that matter is evil and unredeemable. In fact, it rejects the notion of original sin altogether. It accepts the scientific fact that matter and energy (light) are simply distinct ranges of vibration along the same continuum. The sevenfold system of sacraments more admirably expresses this spiritual/chthonic interaction than do the reduced sacramental systems of the Christian Gnostics.

It is to be noted that the traditional Christian sacraments involve the atonement of the individual soul with God, which effects the harmonization of the individual life with Divine Law and integrates the catechumen into Christian society as a “member of the Body of Christ.” In Thelema, the sacraments involve the atonement of the personality with the Self, which effects the harmonization of the individual life with the True Will and integrates the aspirant into Thelemic society as a “member of the body of Initiates.” The Christian apostolic priesthood is the mediating agency of Christ. The Thelemic priesthood is part of the initiating agency of the Masters.

Thus, through the principles of qabalistic syncretism, the traditional sacraments may all have their Thelemic parallels within the E.G.C., where they represent the harmonizing of various aspects of the individual nature with the True Will through the operational modes of the seven planets. A model for such a system of seven sacraments within the E.G.C. is described below.

Baptism (Luna – Yesod)

The ceremony of baptism is mentioned in the final paragraphs of Liber XV, and the Master Therion has left us with notes describing an appropriate baptismal formula for Thelemic use.

Thelema rejects the idea of original sin. So, for us, baptism represents a symbolic birth into the Thelemic community. The child heeds the call of Nuit, who declares, “Do what thou wilt shall be the whole of the Law.” The child enters the portals of Her Church, where he or she is welcomed into the community of worshippers, leaving the profane world and its materialistic obsessions behind.

The baptized child joins the community at what is essentially a probationary level. The recitation of the creed by the congregation during the baptismal ceremony represents the instruction of the child in the essential tenets of the Church. The child is not a full member of the community until he or she has learned these tenets and has made a conscious, informed decision to accept them.

Confirmation (Mercury – Hod)

The ceremony of confirmation is mentioned in the final paragraphs of Liber XV. Confirmation represents the first conscious manifestation of the True Will. The recitation of the creed by the confirmand represents a statement that active participation in the Church and belief in its tenets is in conformity with the confirmand’s own True Will. The Church accepts the confirmand as a Thelemite, one of its own, a rightful claimant to the heirship, communion and benediction of the Saints. The cheirotonia conveys the sacramental bond that joins the confirmand’s consciousness with the egregore of the Church. The cuff on the cheek represents an awakening to the reality of Thelema and all its implications, as well as to the life-consciousness of puberty. (The Greek word egrêgora means, roughly, “it has awakened.”)

Marriage (Venus – Netzach)

The ceremony of marriage is mentioned in the final paragraphs and the ninth Collect of Liber XV. In the case of Apostolic Christianity, holy matrimony expressed the redemption of an otherwise sinful and unclean act through the blessing of the priest, and the dedication of the act to the service of God by bringing new children into the Church in accordance with scripturally acceptable procedures. In Thelema, the Mystery of Marriage is a magical expression of the divine process which continually creates the Universe, the formula of which is “love under will.” The marriage ceremony thus affirms the inherent sacramental nature of sex. It represents the devotion of the most powerful energies of human organic life to the service of the Beloved: the revealer of the True Will.

Ordination (Sol – Tiphereth)

The ceremony of ordination is mentioned in the final paragraphs of Liber XV. In the Roman Catholic and Orthodox systems, holy orders represented the reception of the Holy Spirit in order to act as a mediating agent of God on earth. In the Protestant and Gnostic systems, the Holy Spirit or Gnosis was available to all and did not require the mediation of a Priesthood. The Thelemic E.G.C. recognizes illumination as a continuing, initiatory, evolutionary process. One stage of this process is that of the Lover, Tiphareth — the mediator between Kether and Malkuth, who serves both. The ordinand affirms that it is his or her True Will to enter this intermediate path of dual service; to serve the Masters who have delivered the Law of Thelema to the world, and simultaneously to serve those men and women who seek the freedom provided by this Law.

Will (Mars – Geburah)

While Thelema holds to the principle that spiritual attainment requires effort and struggle, the concept of “penance” or “regretting” has little relevance to us. Our struggle is not against conventional notions of “sin,” but against ignorance, illusion and distraction. Contrition, meekness and self-denial are useless weapons against such enemies– it is the Four Powers of the Sphinx: Knowledge, Will, Courage and Silence, which we must call to our aid. The illusion of original sin has led the Christian churches away from the true significance of self-discipline– it is our task to restore it.

The Christian Sacrament of penance was supposed to effect the expiation of sins committed after the regeneration of baptism. The penitent, recognizing that he had committed a sin, confessed the sin to the priest (in the early church, the confession had to be made before the assembled congregation). He then declared his or her contrition and regret for having sinned, and requested absolution. The priest prescribed a penitential or ascetic activity, which the penitent was to perform as a token of repentance. If the penitent followed the priest’s instructions, it was understood that the sin would be expiated through the mediatory prayer of the priest, and the penitent was free to continue his life with a clear conscience.

In Thelema, the negative concept of “sin” has given way to the positive concept of discovering and accomplishing one’s True Will. As Liber XXX tells us, “Nevertheless have the greatest self-respect, and to that end sin not against thyself. The sin which is unpardonable is knowingly and willfully to reject truth, to fear knowledge lest that knowledge pander not to thy prejudices.” The concept of expiation of sin has been transformed into that of perfection, which should be interpreted not as the achievement of a state of static flawlessness, but rather as an ongoing process whereby one’s fitness for the task at hand (i.e. the accomplishment of the True Will) is increased.

The process of perfection, of striving towards truth, is aptly summarized in the Thelemic rite of “saying Will,” in which the undertaking of any task or activity is related ultimately to the “accomplishment of the Great Work.” The basic rubric of “Will,” as said communally before meals, is set forth in a footnote to Chapter 13 of Magick in Theory and Practice, and this rubric should accompany all communal meals associated with E.G.C. activities. However, the rubric can be adapted to other occasions, as well. The same note states that the point of saying Will is to “… seize every occasion of bringing every available force to bear upon the objective of the assault. It does not matter what the force is (by any standard of judgment) so long as it plays its proper part in securing the success of the general purpose.” Thus, the saying of Will may be adapted to any sphere of activity, individual and communal.

Using this principle, Will can be adapted as a sacramental rite for ecclesiastical, communal use in conjunction with the celebration of the Gnostic Mass, and as such would admirably fill the niche for a formal sacrament attributable to Mars. Rather than the negative struggle against sin embodied by the traditional sacrament of penance, we would have the positive struggle toward Perfection embodied by the sacrament of Will.

The Eucharist (Jupiter – Chesed)

The Eucharist represents the communion of matter and Spirit. Historically, the function of eucharistic rites was the implantation of the seed of Divine Will into the individual body and soul. In the Thelemic E.G.C., the function of the Eucharist is to unite the body and the personality with Divine Consciousness, and symbolically with the True Will. Liber XV is officially appointed for this purpose.

Last Rites (Saturn – Tav/Binah)

While not specifically mentioned in the text of Liber XV, the performance of last rites is specifically provided for by Liber 106, and is recognized in the O.T.O. Bylaws, section 9.05(B). Historically, the purpose of last rites has been to reaffirm the sacramental bond at the point of death in order to assure the dying person a favorable fate in the afterlife. In the Thelemic E.G.C., the purpose of last rites is to help free the dying person from any obstructions which may stand in the way of a free and peaceful death, so that those who approach death may reaffirm the sacramental bond with their own Holy Guardian Angels, and may set their sights squarely on the ultimate accomplishment of their individual True Wills, “whether they will absorption in the Infinite, or to be united with their chosen and preferred, or to be in contemplation, or to be at peace, or to achieve the labour and heroism of incarnation on this planet or another, or in any Star, or aught else.”

Liber 106 is officially appointed for this purpose, and the reading of this book should form the basis of our last rites. Ideally, these last rites should be administered by a priestess, and preferably by a priestess who is also a Dame Companion of the Holy Graal. The reading of Liber 106 may be augmented with additional “provisions,” such as a recitation of the creed, an administration of consecrated wine and a Cake of Light, an anointing with consecrated oil, and any other rites that the dying person may request.

The rite should also be preceded by an informal but detailed discussion regarding the resolution of the dying person’s mundane affairs and matters of conscience. The dying person must be relieved as much as possible of fears, responsibilities, burdens and concerns. The priestess should encourage the dying person to speak freely about anything that is on his or her mind. If necessary, the priestess should be prepared to inform the dying person of arrangements that have been made regarding the estate, and to assist him or her to make any additional arrangements that might be necessary.

References:

- Bricaud, Jean; Catéchisme Gnostique. A l’usage des fidèles de l’Église Catholique Gnostique, Lyon, 1907

- Crowley, Aleister; Book 15: Ecclesiae Gnosticae Catholicae Canon Missae, in Magick: Book IV, Parts I-IV, edited, annotated and introduced by Hymenaeus Beta, Samuel Weiser, York Beach, Maine 1994

- Crowley, Aleister; Book 106: Concernning Death, in The Equinox, Vol III, No. 10, Thelema Publications, New York, 1986

- Crowley, Aleister; Book 837: The Law of Liberty, in The Equinox, Vol III, No. 1, Detroit, 1919 and The Equinox, Vol III, No. 10, Thelema Publications, New York, 1986

- Crowley, Aleister; Mysticism, and Magick in Theory and Practice [1929], in Magick: Book IV, Parts I-IV, edited, annotated and introduced by Hymenaeus Beta, Samuel Weiser, York Beach, Maine 1994

- Higgins, Godfrey; Anacalypsis, an Attempt to Draw Aside the Veil of the Saitic Isis; or, an Inquiry into the Origin of Languages, Nations, and Religions, Longman, Green, et al. London 1836, reprinted by Health Research, Mokelumne Hill, CA 1972

- Hoeller, Stephan A.; The Mystery and Magic of the Eucharist, The Gnostic Press, Hollywood, CA, 1973/1990

- Jackson, Samuel McCauley (Ed. in Chief); The New Schaff-Herzog Encyclopedia of Religious Knowledge, Baker Book House, Grand Rapids, MI 1953

- James, E.O.; The Nature and Function of Priesthood, Barns & Noble, New York, 1955

- James, E.O.; Sacrifice and Sacrament, Thames & Hudson, London, 1962

- Le Forestier, René; L’Occultisme en France aux XIXème et XXème siècles: L’Église Gnostique, Ouvrage inédit publié par Antoine Faivre, Archè, Milano 1990

- McDonald, William J. (Ed. in Chief); New Catholic Encyclopedia, McGraw Hill, NY 1967

- Rudolph, Kurt; Gnosis, Harper & Rowe, San Francisco, 1977

Original Publication Date: 1997

Revised: 2002