(prehistoric/mythic)

by T. Apiryon

The eighth and principal Avatar of the Hindu god Vishnu, the preserver, the eighth child of Vasu-deva and Devaki, the principle expounder of Vedantism. Crowley considered him to be a human being, a Magus of A:. A:., whose Word has survived as INRI. This formula expresses the secret workings of harmonious change within Nature. In this capacity, Crowley identified Krishna with a complex of other mythic figures, especially Dionysus, Osiris, Baldur, Adonis, Attis, Marsyas and Jesus Christ. The word of Krishna as a Magus of Ind was AUM, the Word of Dionysus as a Magus of Hellas was IAO. See Chapter 71 of Liber Aleph and Chapter 7 of The Book of Lies. The name Krishna means “the Dark One,” and he is usually depicted with dark blue skin, and playing a flute.

According to the legend, Kansa, the cruel king of the Yâdavas at Mathura (near Âgra), usurper of his own father’s throne, heard a voice one day which predicted that a child of his sister Devaki would destroy him. In his terror, he went to Devaki and killed the six of her newborn children that he could find. The seventh, Balarâma, though conceived by Devaki, had been, by the grace of the gods, borne by her sister. The eighth, Krishna, born on the vernal equinox, had been smuggled out of Mathura along with his brother Balarâma and switched with the child of a peasant. Kansa noticed that two of Devaki’s children were missing, and ordered the massacre of every strong-looking male child in the city.

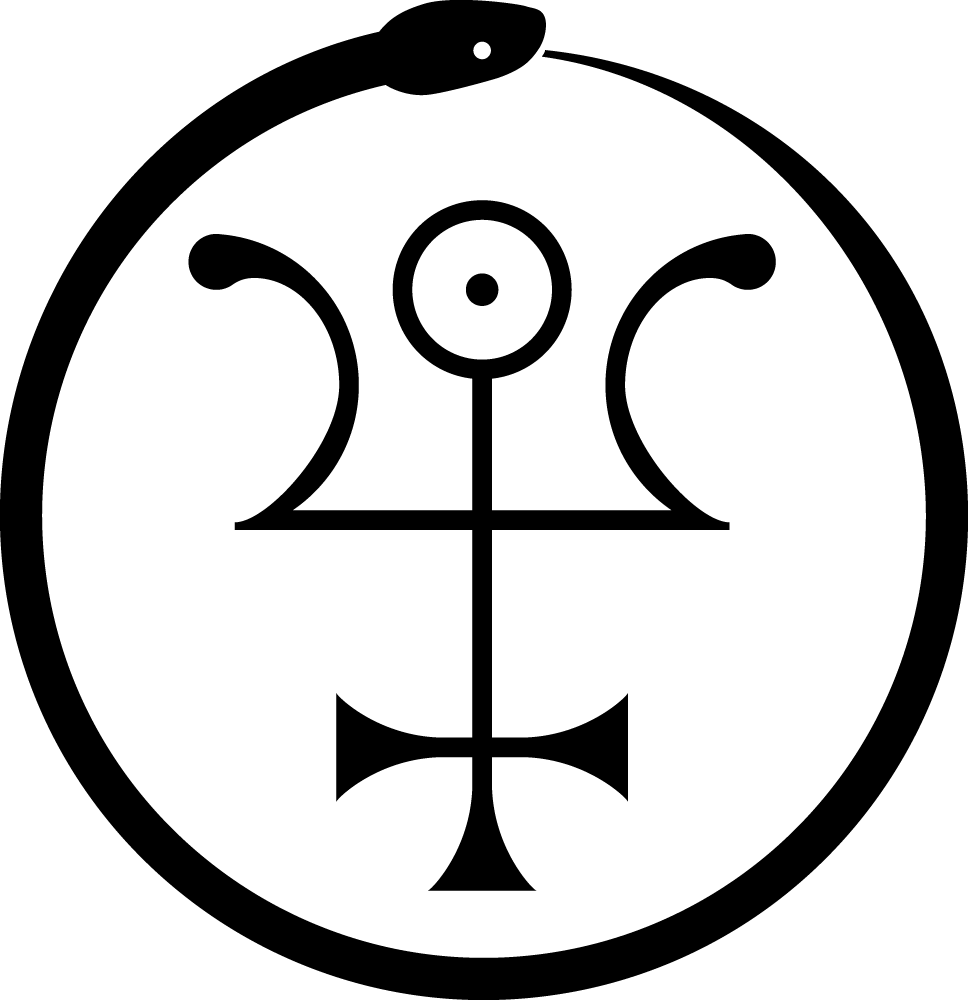

While Kansa massacred the children of Mathura, the infant Krishna lay safely the stable of Nanden, surrounded by cowherds. Brahmâ, Shiva and the other gods visited him to pay him tribute, showering him with flowers. Marked by the gods with a Srivatsa (looped cross) on his breast, Krishna grew up in safety in the country, sporting with milkmaids, playing his flute, disputing with holy men, and engaging in various heroics and pranks. The Hindu “Song of Songs,” the Gîtâ Govinda, contains a type of erotic mysticism couched in the stories of Krishna and the milkmaids.

Kansa, having finally discovered the ruse, determined to lure the two youths to the city, there to capture and slay them. He announced a great tournament, to which all the country folk were invited. The brothers and their fellow cow-herds accepted the invitation and went to Mathura. Krishna, being divine, easily bested all of Kansa’s champions and eluded all of Kansa’s traps. Finally, he leapt up to the dais on which Kansa sat, dragged him down by the hair and killed him.

Krishna assumed his rightful place as ruler of Mathura, then descended into the city of the dead to recover his six slain brothers. With a sudden blast on his conch shell, he so frightened Yama, the lord of death, that he was able to escape with his brothers.

He later became involved in the Mahâbhârata, the great war between the Kurus and the Pândavas, serving as the charioteer of Arjuna, “the Bright One.” At the commencement of the fighting, Arjuna faltered, and told Krishna that he was unable to strike against his beloved brothers the Kurus. Krishna revealed to him the necessity for a warrior to fight, and to abandon personal considerations in the accomplishment of his Dharma (destiny, or true will). Krishna’s exposition to Arjuna is set forth in the Bhagavad Gîtâ, or “Song of God,” which is included in the Liber E and A:. A:. Section 1 reading lists. In 1885, Sir Edward Arnold, author of The Light of Asia, produced an English poetic version of the Bhagavad Gîtâ called “The Song Celestial,” which is included in Section 2 of the A:. A:. reading list. The Bhagavad Gîtâ is one chapter of a larger work, the Mahâbhârata, the complete history of the Great War. The Mahâbhârata is one of the great classics of Hinduism, as well as of human history, and deserves the attention of every Thelemite.

After the great war, Krishna returned to Mathura and eventually died. Seated cross-legged in the forest, he was wounded in his single vulnerable place, his left heel, by an arrow shot by the hunter Jarâ (which means “cold” or “old age”), who had mistaken Krishna for a deer. Krishna pronounced his forgiveness of Jarâ, saying he “knew not what he did,” and sent him to heaven in his own chariot before he died himself.

Having died in the far West of India, Krishna’s bones were carried at the command of Vishnu to Puri, in the far East of India. Here his bones were enshrined, and his worship under the name Jaganath (“Lord of the World,” the origin of our word Juggernaut) was instituted.

References:

Arnold, Sir Edwin; The Song Celestial [1885], Theosophical Publishing House, Wheaton, Ill.

Campbell, Joseph; The Hero with a Thousand Faces, Bollingen Series XVII, Princeton/Bollingen, Princeton NJ 1949/1968

Crowley, Aleister; The Book of Lies [1913], Samuel Weiser, NY 1978

Crowley, Aleister; Liber Aleph vel CXI, The Book of Wisdom or Folly [Thelema Publishing, 1962], Samuel Weiser, York Beach, Maine 1991

Forlong, J.G.R.; Faiths of Man, a Cyclopaedia of Religions [Bernard Quaritch, 1906], University Books, NY 1964

Levi, Eliphas; The Book of Splendours, Samuel Weiser, New York 1973/1984

Masson-Oursel, P. and Louise Morin; “Indian Mythology” in The New Larousse Encyclopedia of Mythology, Hamlyn, NY 1959/1968

Vyasa; The Mahâbhârata, retold and introduced by William Buck, Mentor, New York 1976

Original Publication Date: 5/9/95

Originally published in Red Flame No. 2 – Mystery of Mystery: A Primer of Thelemic Ecclesiastical Gnosticism by Tau Apiryon and Helena; Berkeley, CA 1995 e.v.