(c. 1200 b.c.e./mythic)

by T. Apiryon

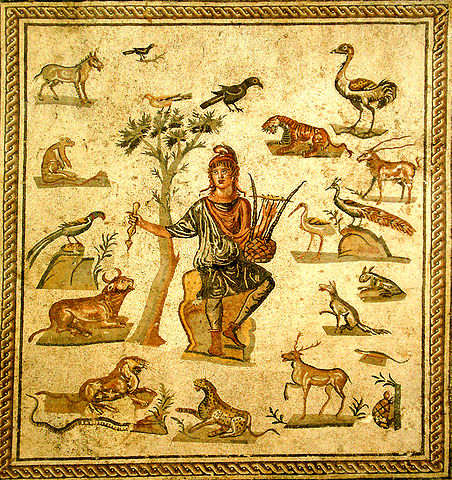

Thracian hero and demi-god; son of Oeagrus (some say Apollo) and Calliope; priest of Dionysus. The most famous of the musicians and poets of Greek mythology. The quintessential Bard, his masterful singing and music upon the Lyre could tame wild animals and move even stones and cliffs. Orpheus journeyed with Jason and the Argonauts on their voyage into the Black Sea in pursuit of the Golden Fleece, where he performed many miracles with his singing, such as charming the Argo down to the sea from the a sand dune where it was beached, calming the moving rocks that would otherwise have crushed the ship and its crew, and lulling to sleep the dragon which guarded the Golden Fleece.

Orpheus married a nymph named Eurydice, to whom he was passionately devoted. One day, Pan (in the form of the bee keeper Aristaeus) spied Eurydice in the forest and pursued her. While fleeing from him, Eurydice was bitten on the heel by a snake; she died and passed into the underworld. Stricken by grief, and finding no satisfaction from his prayers to the gods, Orpheus descended via a cave into the underworld to retrieve her. By the power of his music, he induced Hades and Persephone to allow Eurydice to return with him to the world of the living; but Hades added the condition that he must not look back or she would remain with Hades forever. As he led her from the underworld, he could not help but turn to assure himself that Eurydice was following him, and so lost her. He returned to Thrace alone.

The women of Thrace, perceiving that Orpheus was now available, tried their best to win him, but he repelled their advances. They tolerated his aloofness as long as they could, but one day, no longer able to bear this insult to their feminine powers, they attacked him and tore him to pieces, throwing his head and lyre into the river Hebros. The Muses gathered up the scattered pieces of his body and buried them at Libethra; Zeus took his lyre and placed it among the stars; and his head, singing Eurydice’s name, floated down the Hebros and into the Aegean Sea. Eventually, his head arrived on the coast of Lesbos, where it lodged in a fissure in a rock. It remained there for many years, delivering oracles.

Some versions of the myth say that the Thracian women were Maenads of Dionysus, and that Dionysus commanded them to tear Orpheus to pieces because he had begun to worship Apollo-Helios.

His Thracian origin, his devotion to the Muses, his descent to and return from Hades, and his death by dismemberment show Orpheus to be a human reflection of his god Dionysus; and are the fundamental reasons for his designation as patron of the Greek Mysteries.

Orphism was the first of the organized Hellenic Mystery Schools, and one of the earliest of the fully-developed religious/metaphysical “systems.” It developed in the 6th century b.c.e. and was centered around the teachings attributed to Orpheus as transmitted by a priest named Onomacritus. These were set forth primarily in 24 books of invocatory hymns and included the cosmogony described under Dionysus.

Orphism was a mystical redemption religion based on the allegorical worship of the heavenly bodies, which emphasized the need to separate Dionysiac spirit from Titanic matter. The avowal of the Orphic initiate included the clause, “I am a Child of Earth and Heaven, but my race is of Heaven alone.”

The Orpheans lived in small communes and followed an ascetic lifestyle. Their ascetic practices, including vegetarianism, were intended to symbolize the rejection of the Titanic side of the nature of Man, and to ultimately liberate his spirit from the “tomb of the body” and the “sorrowful wheel of generation.” Orphism adopted and refined the older Dionysian and Bacchic rites, retaining their sacramental and initiatory symbolism and ecstatic mysticism, but tempering their savage frenzy. They replaced the old Dionysian Omophagy, the ritual devouring of the raw flesh of the bull, fawn or goat sacrificed to Dionysus, with the offering and consumption of cakes of meal and honey in commemoration of the slain son of God. Orphism was influential on the thought and works of Heraclitus, Plato, Aeschylus, Sophocles, Pindar and Vergil; and Pythagoras was an Orphic initiate.

References:

Angus, S.; The Mystery-Religions; a Study in the Religious Background of Early Christianity [1925/1928], Dover Publications, NY 1975

Bullfinch, Thomas; The Age of Fable, 1855; republished by Mentor, New York 1962

Detienne, Marcel; “Orpheus” in The Encyclopedia of Religions, Mircea Eliade, Editor in Chief, MacMillan Publishing Co., NY 1987

Forlong, J.G.R.; Faiths of Man, a Cyclopaedia of Religions [Bernard Quaritch, 1906], University Books, NY 1964

Graves, Robert; The Greek Myths, Vol.I, George Braziller, NY 1959

Guirand, F.; “Greek Mythology” in The New Larousse Encyclopedia of Mythology, Hamlyn, NY 1959/1968

Harrison, Jane Ellen; Themis; a Study of the Social Origins of Greek Religion [1912/1927], University Books, NY 1962

Mead, G.R.S.; The Orphic Pantheon, The Alexandrian Press, Edmonds, Washington 1984

Ovid; Metamorphoses, translated by Rolfe Humphries, Indiana University Press, Bloomington 1955/1973

Puhvel, Jaan; Comparative Mythology, Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore 1987

Webb, James; The Occult Underground, Library Press, LaSalle, Illinois 1974

Wili, Walter; “The Orphic Mysteries and the Greek Spirit” [1944] in The Mysteries, Papers from the Eranos Yearbooks, Bollingen Series XXX.2, edited by Joseph Campbell, Princeton/Bollingen, Princeton NJ 1955/1978

Zimmerman, J.E.; Dictionary of Classical Mythology, Harper & Row, NY 1964

Original Publication Date: 5/11/95

Originally published in Red Flame No. 2 – Mystery of Mystery: A Primer of Thelemic Ecclesiastical Gnosticism by Tau Apiryon and Helena; Berkeley, CA 1995 e.v.