Introduction to the Gnostic Mass

by T. Apiryon

Aleister Crowley wrote Liber XV, the Gnostic Mass, in 1913 in Moscow, the year after his appointment by Theodor Reuss as the X° Head of the British Section of O.T.O. According to W.B. Crow, he wrote it “under the influence of the Liturgy of St. Basil of the Russian Church.” Crowley published the Gnostic Mass three times during his life: in 1918 in The International, in 1919 in The Equinox, Volume III, No. 1 (the “Blue Equinox”), and in 1929/30 in Appendix VI of Magick in Theory and Practice (“MTP”). Theodor Reuss published a German variant in 1918. Crowley conducted ceremonies in Cefalù that incorporated portions of the Gnostic Mass, but the first recorded public celebration of the Gnostic Mass proper was on Sunday, March 19, 1933 e.v., by Wilfred T. Smith and Regina Kahl in Hollywood, California. Crowley writes in Chapter 73 of his Confessions:

During this period 1 the full interpretation of the central mystery of freemasonry became clear in consciousness, and I expressed it in dramatic form in `The Ship’. The lyrical climax is in some respects my supreme achievement in invocation; in fact, the chorus beginning:

Thou who art I beyond all I am…

seemed to me worthy to be introduced as the anthem into the Ritual of the Gnostic Catholic Church, which, later in the year, I prepared for the use of the O.T.O., the central ceremony of its public and private celebration, corresponding to the Mass of the Roman Catholic Church.

While dealing with this subject I may as well outline its scope completely. Human nature demands (in the case of most people) the satisfaction of the religious instinct, and, to very many, this may best be done by ceremonial means. I wished therefore to construct a ritual through which people might enter into ecstasy as they have always done under the influence of appropriate ritual. In recent years, there has been an increasing failure to attain this object, because the established cults shock their intellectual convictions and outrage their common sense. Thus their minds criticize their enthusiasm; they are unable to consummate the union of their individual souls with the universal soul as a bridegroom would be to consummate his marriage if his love were constantly reminded that its assumptions were intellectually absurd.

I resolved that my Ritual should celebrate the sublimity of the operation of universal forces without introducing disputable metaphysical theories. I would neither make nor imply any statement about nature which would not be endorsed by the most materialistic man of science. On the surface this may sound difficult; but in practice I found it perfectly simple to combine the most rigidly rational conceptions of phenomena with the most exalted and enthusiastic celebration of their sublimity.

The word “Mass,” according to the Roman Catholic Church, comes from the Latin word Missa, “dismissal,” from the phrase used at the completion of some old liturgies, “Ite, missa est” (“Go, this is the dismissal”). Despite the origin of its name, the eucharistic ceremony of the Mass did not originate with Christianity, nor is it the exclusive property of any single religion. Crowley recognized in the Liturgies of the Roman and Russian Rites the intricate and beautiful patterns of a profound symbolic tradition, glimmering beneath the layered crust of scholastic religious dogma.

The eucharistic ritual which comprises the core of the Mass is far older than Christianity; in fact, some Protestant theologians have pointed to the Mass and its symbolic components as evidence of the corruption of the Catholic Church by the incorporation of “idolatrous” pagan practices and doctrines. A few of the many examples of this include: the round Host and Paten conjoined with the silver crescent of the Chalice as obvious symbols of Sun and Moon; the Altar Cross as Cult Object (Omphalos, Linga or Sacred Tree); the baptismal font as sacred spring; the Litany of Saints an invocation of the spirits of the ancestors; and the Eucharist itself as a vestige of human sacrifice.

Some prehistoric totemic cults, by the evidence of certain modern totemic cults, may have created a sense of social bonding through ritual feasts, especially feasts which involved the consumption of the totem animal or plant. The Magic which entwined the destinies of the members of the totem-society with that of the totem animal or plant also entwined the destinies of the members of the totem-society with each other.

The sense of shared destiny, or shared Spirit or Magic, became so strong in some totemic cults that it began to take on its own unique identity, with its own attributes and even its own personality. Sometimes it would become closely identified with the personality of a particularly virtuous and powerful hero or shaman, an identification which would remain after the hero’s death. The hero, identified with the cult Spirit, could not have been said to have truly died so long as the cult itself survived. He had become a divine man, a hybrid between mankind and the forces of nature, fully human yet also fully divine, who was dead and yet alive, who therefore possessed power over death and life.

The early worship of Dionysus, which may have developed in a similar way from the rites of a totemic society, included the drinking of wine and the consumption of the raw flesh of a sacrificial animal in a ritual called the Omophagia. The animal was either a bull, a fawn or a goat, all sacred to Dionysus in different locales, and it was ritually torn apart in commemoration of the dismemberment of Dionysus-Zagreus, the infant son of Zeus, at the hands of the Titans.

The flesh consumed in the wild Orgia of the Bacchantes was not, however, the mere flesh of a butchered animal. First, it was an animal of a type which was sacred to the God (i.e. a totem animal) and thus partaking of the God’s vital nature. Second, the animal had ceremonially passed through the God’s own greatest and most characterizing ordeal. By passing through this ritual of sympathetic magic, the animal was considered to have assumed the actual identity of the God. Its flesh, therefore, was believed to have become the very flesh of Dionysus himself. The vine was also sacred to Dionysus, and partook of his nature in a similar, totemic way. When the Bacchantes consumed the flesh and the wine, they consumed the actual body and blood of their God. By integrating the body of their God into the fabric of their own individual bodies, they effected the integration of the Spirit of God into the fabric of their own individual Spirits. This not only gave them access to the power and Magic of the God, it also gave them a strong sense of identity with their fellow Bacchantes, who were infused with the same divine Spirit. 2

Over time, Greek culture became more refined and complex through intercourse with other cultures, such as those of Egypt, Asia Minor and Phoenicia. The primitive worship of Dionysus survived because it was itself amenable to evolution and development.

The Orpheans (who flourished in the 6th century p.e.v.) adopted the Dionysian religion as their own. They tempered the savagery of its rites, and used these refined rites to convey, by allegory, the philosophical teachings of their redemptive religion. Being ascetics and vegetarians, they substituted for the bloody Omophagia a bloodless sacramental communion of cakes made of meal and honey in remembrance of the slain son of God. The Orphic teachings, preserved in the Orphic Hymns and developed in the Greek Mysteries and the teachings of the most famous of the Orphic initiates, Pythagoras, exerted a great deal of influence on the development of later Hellenic religion and philosophy, particularly Neoplatonism and Gnosticism. By these routes they entered that highly successful syncretistic religion known as Christianity.

The word “Gnostic” is a Greek word which means “pertaining to knowledge.” It is often used in reference to a group of early Christian religious systems which developed in the cultural, religious and philosophical melting pot of the Eastern Roman Empire during the first century, e.v. and were centered primarily in Alexandria, Egypt. Known collectively as Gnosticism, these systems, considered “heresies” by the developing Christian theocracy, attempted to fuse Judaic Christianity with Greek Philosophy, Egyptian Theurgy and other elements. Such systems included the teachings of Simon Magus, Basilides, Valentinus, Bardesanes and Marcion, as well as those of the groups known as Sethians and Naasenes. The term “Gnostic” may also be used to refer to other religious systems which, though non-Christian, shared many of the views of the Christian Gnostics. The Orphean religion was among these, so were the Hermetic teachings of the Egyptian Poimandres sect and the Manichaean religion, and so is the religion of the Mandaeans of southern Iraq.

In comparing the diverse patterns of the Gnostic tapestry, we note a few common threads:

-

symbolic and practical syncretism;

-

a cosmogony in which Matter is separated from Spirit by a series of emanations or Aeons, with the cosmos originating in a “mixture” of Spirit into Matter;

-

varying degrees of anti-cosmic sentiment: devaluation of the created world and of material existence, expressed in either ascetism or libertinism;

-

the doctrine that the human spirit is essentially divine;

-

a system of redemption through mysticism and personal enlightenment which is represented in a soteriology of the “redeemed redeemer”; and

-

an eschatology emphasizing the ultimate separation of the justified Souls from Matter and their return to pure Spirit.

Many, but not all, of the Gnostic systems placed the True God above the God worshipped by the great mass of humanity. This inferior God was often portrayed as an arrogant and tyrannical power, ignorant of its own origin and limitations. A number of Gnostic systems were characterized by an emphasis on the divine female counterpart to the Christos-figure, who was variously known as Sophia, Helena, Ennoia, or Barbêlô.

The elitism of most Gnostic systems led to their ultimate extinction in favor of the more populist and militant “orthodox” systems of Christianity, Islam and Zoroastrianism; and many of the original writings of the Gnostics were systematically destroyed. Some, however, have survived, notably the Corpus Hermeticum, the “Askew Codex,” the “Bruce Codex,” the “Akhmim Codex” and the Nag Hammadi Library, as well as the extant writings of the Manichaeans and Mandaeans. Much more information concerning the doctrines and beliefs of various forms of early Gnosticism have been transmitted by the writings of the early Christian anti-heretical writers such as Justin Martyr (c.100-c.165 e.v.), Irenaeus of Lyons (c.100-203 e.v.), Clement of Alexandria (c.155-c.210 e.v.), Tertullian of Carthage (c.155-c.230 e.v.), Hippolytus of Rome (170-235 e.v.) and Epiphanius of Salamis (315-403 e.v.), the last being a less reliable source than the others.

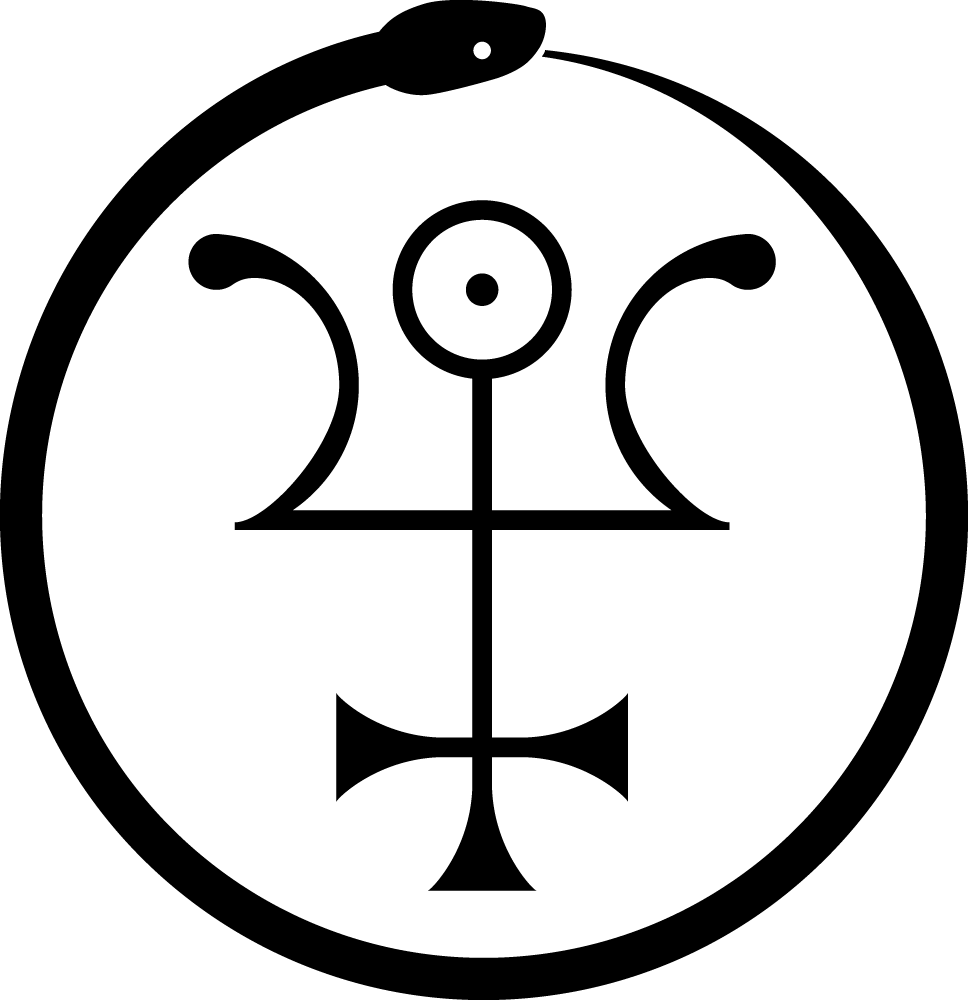

In addition to its transmission through literature, the Gnostic current appears to have wound its way through the middle ages in several distinct streams of tradition. The Hermetic Gnosis was incorporated into the allegorical science of Alchemy. Egyptian Gnosticism influenced Hebrew Hekalot and Merkabah mysticism which later developed into Qabalism. The Marcionite, and possibly Manichaean, Gnosis was preserved by the Paulicians of Armenia and possibly influenced the Bogomils of Bulgaria, who, in turn, helped to found the Cathar or Albigensian sects of Southern France in the 12 century. Catharism further influenced the development of medieval Jewish Qabalism as well as the chivalric legends of the Holy Grail, and united with esoteric Islamic ideas (with their own Gnostic and/or Neoplatonic influences) in the unorthodox Christianity of the Knights Templars. Kabbalism, Hermeticism and Templarism united in Rosicrucianism and Freemasonry; which formed the foundation for O.T.O., the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn and the A:. A:. The Valentinian Gnosis passed quietly into the structure and sacramental rituals of the Roman Catholic Church.

Discoveries of some of the Gnostic codices, the Elenchos of Hippolytus, and certain Cathar documents inspired the French Gnostic revival of the late 19th century e.v. The French Gnostic Revival blended elements of Templarism, Rosicrucianism, Church Christianity and historical Gnosticism in an attempt to reconstruct an independent Gnostic Church, one of the results of this was the foundation of our own Gnostic Catholic Church.

The union of the Gnostic Catholic Church and O.T.O. represented, therefore, a confluence of numerous Gnostic streams into a single body– a body which was to achieve ultimate fruition upon the introduction of the last and most dynamic Gnostic current, the Law of Thelema, which was introduced into the O.T.O. and Gnostic Catholic Church by the Master Therion.

In composing Liber XV, Crowley attempted to uncover the hidden Gnostic tradition concealed within the ceremony of the Mass, to liberate it from bondage to the Scholastic theories and dogmas of Christian theology, and to demonstrate the fundamental continuity between this ancient tradition of Wisdom and the modern revelations and liberating philosophy of Thelema.

Go to The Gnostic Mass.

Notes:

- The summer of 1913 e.v.

- The same Magic was wrought by the ancient Persians through the ritual consumption of the sacred Haoma drink, and by the Vedic Aryans with their Soma.

References:

-

Angus, S.; The Mystery-Religions; a Study in the Religious Background of Early Christianity [1925/1928], Dover Publications, NY 1975

-

Cammell, Charles Richard; Aleister Crowley: the Man, the Mage, the Poet, University Books, Inc., New Hyde Park, NY 1962

-

Couliano, Ioan P.; The Tree of Gnosis: Gnostic Mythology from Early Christianity to Modern Nihilism, Harper San Francisco 1990

-

Crow, W.B.; A History of Magic, Witchcraft and Occultism, Aquarian Press, London 1968

-

Crowley, Aleister; The Confessions of Aleister Crowley: an Autohagiography, edited by John Symonds and Kenneth Grant, Routledge and Kegan Paul, London 1979

-

Crowley, Aleister; Magick in Theory and Practice [1929/30], in Magick: Book IV, Parts I-IV, edited, annotated and introduced by Hymenaeus Beta, Samuel Weiser, York Beach, Maine 1994

-

Drower, E.S.; Water into Wine: A Study of Ritual Idiom in the Middle East, John Murray, London 1956

-

Eliade, Mircea (Editor in Chief); The Encyclopedia of Religions, MacMillan Publishing Co., NY 1987

-

Eliade, Mircea; Rites and Symbols of Initiation: the Mysteries of Birth and Rebirth, Harper & Row, NY 1958

-

Forlong, J.G.R.; Faiths of Man, a Cyclopaedia of Religions [Bernard Quaritch, 1906], University Books, NY 1964

-

Forlong, J.G.R.; Rivers of Life, London 1883

-

Frazer, James G.; The Golden Bough; the Roots of Religion and Folklore [1890], Avenel Books, NY 1981

-

Gaster, Theodor H.; The New Golden Bough; a New Abridgment of the Classic Work by Sir James George Frazer; Mentor Books, NY 1959

-

Graham, Lloyd M.; Deceptions and Myths of the Bible, Citadel Press, NY 1975

-

Guirand, F.; “Greek Mythology” in The New Larousse Encyclopedia of Mythology, Hamlyn, NY 1959/1968

-

Harrison, Jane Ellen; Themis; a Study of the Social Origins of Greek Religion [1912/1927], University Books, NY 1962

-

Hislop, Rev. Alexander; The Two Babylons, or, The Papal Worship, Loizeaux Bros., New Jersey 1916, 1959

-

Hymenaeus Beta, ed.; The Equinox, Vol. III, No. 10, Thelema Publications, NY 1986

-

Inman, Thomas; Ancient Pagan and Modern Christian Symbolism [1869/1874], Kessinger Publications, Kila, MT 1993

-

James, E.O.; Sacrifice and Sacrament, Thames and Hudson, London 1962

-

Legge, Francis; Forerunners and Rivals of Christianity, from 330 B.C. to 330 A.D. [1915], University Books, NY 1964

-

Mead, G.R.S.; Fragments of a Faith Forgotten [1900], University Books, NY

-

Mead, G.R.S.; The Orphic Pantheon, The Alexandrian Press, Edmonds, Washington 1984

-

Puhvel, Jaan; Comparative Mythology, Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore 1987

-

Rudolph, Kurt; Gnosis, Harper & Rowe, San Francisco, 1977

-

Scholem, Gershom; Origins of the Kabbalah [1962], Jewish Publication Society/Princeton University Press, New Jersey 1987

-

Starr, Martin P.; The Unknown God: W.T. Smith and the Thelemites, Teitan Press, Bolingbrook, Illinois 2003

Original Publication Date: 1995

Updated: 2010

Originally published in Red Flame No. 2 – Mystery of Mystery: A Primer of Thelemic Ecclesiastical Gnosticism by Tau Apiryon and Helena; Berkeley, CA 1995 e.v. Several minor errors have been corrected since publication in the Red Flame; notably the following:

- Reuss’s translation of the Gnostic Mass was published in 1918 rather than 1920.

- A mention of Crowley’s Cefalù ceremonies incorporating elements from the Gnostic Mass was added.